Meniscal transplantation in patients with ‘substantial’ articular cartilage damage.

Meniscal allograft transplantation in patients with substantial cartilage disease led to a sustained long-term improvement in patient-reported outcome measures

Imran Ahmed, Chetan Khatri, Tim Spalding, Nick Smith

Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/ksa.12536

Meniscal transplantation involves replacing a missing meniscus with a new meniscus from a donor. This is not a new thing – the first case series of meniscal transplants was actually published all the way back in 1988! The first meniscal transplants in the UK were performed by Mr Angus Strover, who I was lucky enough to have as my mentor. I performed my first solo meniscal transplant all the way back in 2008, and since then I’ve performed well over 100 transplants.

|

|

|

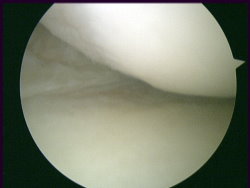

Patient with a completely missing |

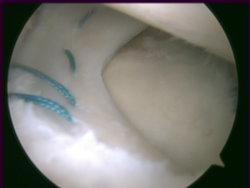

Meniscal allograft surgically |

Meniscal transplantation is a very difficult, complex and ‘fiddly’ operation, and it is only undertaken (in any serious numbers) by a fairly small cohort of specialist knee surgeons.

The reason that only a relatively small number of meniscal transplants are actually performed, despite the fact that so many people tear and end up losing their meniscal cartilages, is that the clinical indications (inclusion and exclusion criteria) for meniscal transplantation are very specific and quite tight. Two of the big questions in meniscal transplantation are ‘When to actually go ahead with a meniscal transplant?’, and also ‘At what point is the damage simply too far gone?’

It is generally accepted that the sooner you catch someone who is suitable for a meniscal transplant, and the earlier you proceed with the surgery, then the better the outcome (both in the short-term and the longer-term) is likely to be.

In this study by Tim Spalding, Nick Smith and the team in Coventry, they used their prospective meniscal transplant register to retrospectively look back at patients, to compare the outcomes of those patients with more-minor cartilage damage vs those with ‘more substantial’ cartilage damage / loss, with ‘more substantial’ being defined as International Cartilage Repair Society (ICRS) classification 3b cartilage damage (“a cartilage lesion that extends more than 50% of the cartilage thickness, reaching down to the calcified layer of cartilage, but not fully exposing the underlying subchondral bone”).

The team looked at 422 patients, with a mean follow-up of 6.33 years (s.d. 3.48). 129 patients were found to have less severe chondral lesions and 281 patients had ‘more substantial’ cartilage damage/loss.

There was no significant difference in PROMs between the two groups, up to 10 years post-operatively (p > 0.05). The ‘substantial cartilage damage’ group, however, had significantly lower survival rates compared to those without (81% vs 94%).

What does this mean?

As always, there are two ways to look at any situation: ‘Glass half empty or glass half full’…

One could say that even though patient reported outcomes are equally good, the failure rate after meniscal transplantation is roughly doubled if there is substantial articular cartilage damage / loss at the time of the meniscal replacement surgery.

Alternatively, one could say that the success rate for meniscal transplantation is still about 80% at roughly 5-year follow-up even if the patient has substantial articular cartilage damage in that compartment of their knee… which is a pretty good outcome for what should best be described as salvage surgery in someone with a really bad knee who is desperate for help with a solution other than artificial joint replacement surgery.

This really useful article simply gives us further information to help guide us with our decision-making when it comes to who may or may not be suitable for a meniscal transplant, and importantly, it adds to the volume of evidence that we can present to potential / prospective patients to help better-inform them of the safety / efficacy of the options available to them.

READ MORE about meniscal transplantation