Should I keep running if my knees hurt?

There have been quite a few statements recently, both in papers and on social media, stating that if your knee(s) hurt when you’re running, then you should continue running, and suggesting that people who tell you to stop running A) don’t know what they’re talking about, and B) could actually be doing you harm!

So, are these people right? The answer is fairly simple. There ARE certain instances where the correct advice is indeed to stop (or at least cut down on) running, and there is simple but sound scientific evidence to back this up.

Not everyone is born to run

If you’ve got normal knees, if your posture and control are good, and if you’re not too overweight, then running can be fantastically good for you. However, it’s important to acknowledge that some people are just born to run… whilst some people are simply not! Some people can run for many years, into old age, with no significant problems at all. However, some people simply aren’t that lucky!

No gain, without pain?

Pain is your body’s way of letting you know that there’s a potential problem. ‘No pain, no gain’ is absolutely correct when it comes to the pain of cardio fitness workouts. However, pain in a joint can often be a sign of a specific issue, and like many issues in life, if you simply ignore it then it’s probably just going to get worse.

How to find out the cause of your knee pain

The important thing here is to find out what, specifically, is causing your actual pain – as pain is just a symptom, not a diagnosis… and anyone with any significant knee pain that’s enough to bother them really needs a diagnosis before you can safely or sensibly offer any kind of advice, whether that be specific exercise advice or any kind of actual treatment.

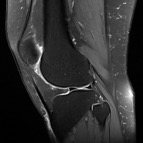

A good physiotherapist will be able to diagnose many knee ‘ailments’ quite accurately. However, for anything where a patient’s symptoms are more severe / significant or persistent, and certainly where there is any concern at all, then you are most probably going to need imaging to confirm what the actual problem inside the knee might actually be.

The importance of imaging

Importantly, as a Knee Surgeon I only operate on about 25% of the patients that I see in clinic, with the other 75% not needing surgery, but potentially needing other non-invasive treatments instead. However, every patient gets a clear and specific diagnosis, and an appropriate treatment plan, and appropriate imaging is a key component of this.

The various types of imaging that we may send patients for can include:

- X-rays

- Ultrasound scans

- MRI scans

- CT scans

- Bone-SPECT scans

- Blood tests

- Bone density scans

Common (but ‘non-damaging’) causes of pain at the front of the knee

A lot of the runners that I see in clinic tend to complain of pain at the front of their knees when running. Rather unimaginatively, this is sometimes referred to by some people as ‘runner’s knee’. However, this is not a proper medical diagnosis! Some people also use the term ‘patellofemoral pain syndrome’ – again, this is an over-simplistic catch-all phrase that again, isn’t really a proper specific diagnosis.

Many of the things that can cause knee pain when running can be relatively minor, and fairly ‘non-damaging’, such as:

- Patellar tendinopathy

- Quadriceps tendinopathy

- Fat pad inflammation

- Iliotibial band (ITB) friction syndrome

and these issues rarely ever end up needing any kind of surgical intervention, and they do not lead to an increased risk of future arthritis.

Articular cartilage damage (wear & tear) in the joint is more serious!

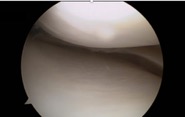

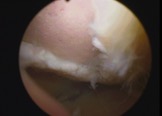

However, one very common cause of pain at the front of the knee is if there is articular cartilage damage in the patellofemoral joint – which means that there is wear and tear / thinning / loss of the smooth white shiny layer of cartilage that normal covers the joint surfaces; particularly on the back of the kneecap (the patella) and the groove at the front of the femur (the trochlear groove) in which the kneecap moves up and down as the knee bends and straightens. Articular cartilage has no blood supply and it does not grow back / repair / heal / regenerate on its own, and articular cartilage damage is something that only ever tends to get worse with time, not better. If the articular cartilage wears away completely, to leave bare bone exposed, then that is what we refer to as osteoarthritis in the joint – and this leads to increasing pain, stiffness and swelling, and a gradual progressive loss of function, eventually leading to artificial joint replacement surgery (which is a big deal!)

The biomechanics of running and how it affects the knee joint

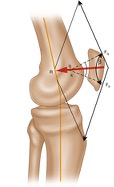

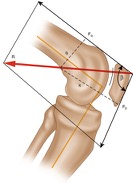

The patella acts as a fulcrum at the front of the knee joint, specifically increasing the moment arm (the ‘lever arm’ and hence the pull) of the quadriceps, particularly in early flexion, meaning that the pull of the quads is more effective at preventing the knee bending when the joint is loaded. Importantly, the forces involved that pass through the patellofemoral joint with knee loading are absolutely massive, and these forces increase as the joint is flexed and with the weight of loading, and also with impact. Patellofemoral loading has been calculated as being:

- 3 x body-weight with ambulation

- 3 x body-weight with stairs

- 6 x body-weight with running and

- 8 x body-weight with deep squatting.

By comparison… patellofemoral compressive forces during ergometric cycling have been calculated as being approximately 0.4 x body-weight – that’s approximately x 14 less than the patellofemoral loading seen when running!

What to avoid if your knee joints are severely damaged

If you have got significant damage in a knee joint, particularly in the patellofemoral compartment at the front of the knee, then the most sensible exercise advice is to avoid anything that involves unduly heavy / repetitive patellofemoral loading. This means keeping clear of impact running, but also avoiding:

- deep squats

- heavy loaded squats

- lunges and

- heavy weights.

Can you build up muscle strength to ‘protect’ your knees?

Telling someone to ‘build up your muscle strength to protect your knee’ can sometimes be misguided and inappropriate….

If you’ve torn a ligament in your knee, like the ACL or the PCL, then it’s important to build up muscle strength and speed up proprioceptive reflexes in order to improve dynamic stability… and this alone may be sufficient for the patient to be able to avoid the pain, hassle and risks of ligament reconstruction surgery.

However, if you’ve got ‘wear and tear’ in a joint (i.e. articular cartilage damage / thinning / loss), then the last thing you want to do is to heavily and excessively load that joint. You can’t build up muscle strength and bulk without heavily loading a muscle… and you can’t heavily load the muscles around a knee joint without heavily loading the joint itself.

Therefore, if there is degenerative damage in a joint, then the best, safest and most appropriate approach is to avoid heavy loading and impact, and not to try and focus on building up muscle bulk, but to focus on light, non-impact, non-pivoting cardio fitness work instead.

What’s the alternative if you do have to stop running?

One of the challenges I face as a knee surgeon is sometimes having to tell a runner what they least want to hear – i.e. to stop running. This will be purely for their own good, because it will be the best way to stop / reduce the pain in their knee and make the knee joint last longer.

However, cutting down or even stopping running does not mean stopping exercise. Continuing with exercise of some shape or form is vital … but there are a lot of things that are good for your heart and your health that are better for your knees than running. This includes:

- gentle walking (avoiding steep hills)

- cycling / the exercise bike, with the seat up high and the resistance down low,

- the cross-country ski version of the cross-trainer (not the Stairmaster), and

- swimming, with mainly front-crawl / back-stroke (rather than breast-stroke legs).

IN SUMMARY

1. Listen to your knees: if whatever you’re doing makes them hurt, then stop and try something else instead.

2. If you’re suffering from significant knee symptoms, then see either a physiotherapist or a specialist doctor / surgeon who can give you a specific diagnosis – you need a diagnosis before you can even start talking about specific treatment options.

3. Accurate specific diagnosis very often requires imaging, with X-rays and / or scans.

4. If you’ve got significant cartilage damage in your knee, then you’re far better off doing non-impact exercise, such as cycling, rather than running.

5. And finally, if a knee surgeon advises you against continuing with running, it’s normally for very good reasons, and they’re simply trying to help make your knee hurt less and last longer, and not just upset you purely for the sake of it!

Mr Ian McDermott, 24th Jan 2021