This is the story of a 24-year-old girl who injured her left knee skiing at the beginning of the year. This young lady had the classic ski injury where she caught her ski, she twisted her knee and her bindings failed to come off. With this lady’s injury, however, she did not notice any pop or snap at the time, and there was pain initially, but this was not actually overly severe. However, the patient was then unable to weight-bear, and she ended up having to be evac’d off the slope.

The patient was seen by an orthopaedic surgeon near the resort. She had an MRI of her knee and she was told that she had torn her ACL, and that she would need surgery.

I saw the lady myself about just over 1 week after the date of her injury. At that stage she was walking slowly, with the help of 2 crutches, although she was able to tentatively fully-weight-bear without. She had a cricket pad splint on her knee and, not surprisingly, the knee was stiff, with a roughly 5-degree block from full extension, and with flexion limited to a maximum of about 85 degrees. The whole knee was just slightly swollen. Importantly, the anterior drawer test was negative; however, I emphasised to the patient that it is not uncommon to have a negative anterior drawer early on after an ACL injury, with this potentially being a false negative, because of tension in the muscles from guarding due to pain and apprehension. The collateral ligaments felt stable, but the knee was way too stiff and uncomfortable to even attempt to McMurray’s test.

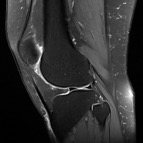

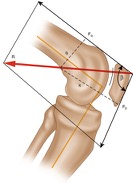

The patient’s MRI scan (taken abroad) showed the following:-

- There was what appeared to be a definite tear of the ACL.

- Of note, the orientation of the PCL looked normal.

- There were partials tears of both the medial collateral ligament and the lateral collateral ligament.

- Thankfully, there was no evidence of any meniscal tears.

|

|

Sagittal view showing torn ACL (looks like a complete or perhaps, at least, a subtotal tear). |

|

|

Of note: the orientation of PCL actually looks normal. |

|

|

Coronal view. |

As is appropriate in these cases, I advised the patient to take care with her knee and I referred her across to one of our excellent local physiotherapists to start some very gentle cautious slowly-progressive rehab treatments on her knee.

I reviewed the patient at the 6-week post- injury mark. At that stage, she was actually walking nice and fast, with a steady even gait. There was minimal residual swelling in the knee and there was only slight generalised muscle wasting in the leg. The lady had an almost full range of motion in her knee, with full extension and lacking just the last 5 degrees only of full deep flexion. Importantly, with the anterior drawer test there was still literally just 1 or 2 millimetres of anterior laxity compared to the other knee, with a solid anterior endpoint still. A Lelli’s levers test for ACL deficiency seemed to be negative. The PCL, the collateral ligaments and posterolateral corner all felt fine, and a McMurray’s test was negative.

I advised the patient to continue with her rehab.

I then reviewed the patient again at the 3-month post-injury mark. By this stage, the patient stated that she felt that her knee was still improving. Sensibly, the patient had not attempted any impact or twisting through her knee yet, and she was still taking things very cautiously with her rehab sessions; however, the patient had stated that her knee felt reasonably stable, and that she had not suffered any episodes of impending or actual giving way at all.

The clinical examination showed that the there was still literally just 1 or 2mm only of increased anterior laxity in the injured knee, compared to the other side, but with a good solid anterior endpoint still.

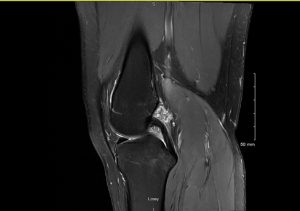

A repeat MRI scan of the patient’s knee at this stage looked surprisingly good, and this showed clear evidence of a large proportion of the fibres of the anterior cruciate ligament still remaining in-continuity. Also, the orientation of the PCL still looked normal (this is a sign that shows that there is no significant anterior tibial subluxation, which itself is an indirect sign that there is still tension remaining in the fibres of the ACL).

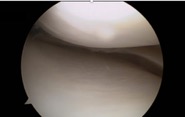

Repeat MRI scan from 3 months post-injury

|

|

Sagittal view showing significant healing of the ACL. |

|

|

Orientation of PCL still looks normal. |

|

|

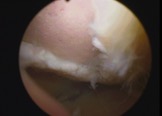

Coronal view. |

Currently, the patient is just slowly ramping things up with her physio rehab treatments, and she is very happy not to have to undergo a surgical ligament reconstruction on her knee (with all the additional pain, hassle, time off work, risks and the prolonged rehab that this would have entailed).

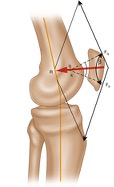

The patient does want to go back to volleyball and bouldering (although sensibly, she has decided against ever going back to skiing again). I have advised her to do a further 3 months of rehab, plus the patient has also now got herself a decent ACL brace (and Össur CTi ACL brace), which she is planning to wear once she does start going back to higher-risk activities (with impact and twisting through her knee).

I have referred the patient to our Research Physio, Mr Anthony Tang, in the Research and Outcomes Centre at our clinic at 31 Old Broad Street, for her to have a full functional testing session.

I am going to review the patient back in clinic in a further 3 months’ time (at the 6-month post-injury mark), with her having a functional outcomes testing session again immediately beforehand… but at this stage I am reasonably confident that this young lady will continue to do well enough for her not to actually need any surgery on her knee.

What does this case highlight?

- First, hopefully this case highlights the importance and value of taking an appropriately slow, calm and measured approach to this kind of knee injury. Importantly, if a patient is doing well with early rehab after an ACL injury, then for as long as they continue to make good progress, there is a good argument for delaying any decisions about any potential surgery, and for simply continuing with the rehab.

- Next, even though the patient’s initial MRI scan appeared to show what looked like a subtotal total or maybe even total ACL tear, the subsequent follow-up MRI 3 months later showed very clearly that this must actually have been just a major partial It is important to remember that an MRI scan is not a photograph: instead, it is simply a set of 2D representations of the % water content at any specific pixel location on the screen. Different tissues have a different % water content, and hence show up as varying shades of grey. When an ACL is damaged, with a partial tear, there is blood in the ligament and the ligament is swollen / oedematous, and hence (due to the increased water content within the ligament) the ligament will look pale and ill-distinct. Importantly, on numerous occasions now, I have seen scans where the initial scan looks really bad, but where a subsequent scan looks significantly better. This is not a case of a completely torn ACL miraculously somehow growing back, reattaching and re-tensioning itself: instead, what this actually highlights is that there is a not-insignificant false positive rate for the radiological diagnosis of an ACL tear from MRI, and this also emphasises the importance of treating the patient, not the picture.

- The decision as to whether to perform a surgical ACL reconstruction (particularly on a young sporty female) or whether to attempt surgical management is very often not 100% clear-cut or straightforward. What this case hopefully highlights, however, is the value of patience, and of not simply rushing straight in with surgery.

(With thanks to the patient, who kindly allowed me to share this.)